In honor of Arthur C. Clarke, who understood the destination before the rest of us saw the road.

Something is ending. Something else is beginning. And almost nobody is paying attention to the connection between the two.

On one side: birth rates collapsing across every wealthy nation on earth. South Korea at 0.72 children per woman. Japan, Italy, Spain, all below 1.2. The United States, once the demographic engine of the Western world, quietly running below replacement. China, with 1.4 billion people, producing children at the rate of 1.0 per woman and falling.

On the other side: artificial intelligence growing at a rate that has no historical precendant. ChatGPT launched in November 2022 with one million users in its first week. By February 2026, less than 40 months later, it has over 800 million weekly active users. That is not growth. That is a detonation.

The two curves are running in opposite directions. And they are not unrelated.

The Baseline: What Actually Happened

To understand where we are going, you have to be precise about what already occurred.

November 30, 2022. OpenAI releases ChatGPT as a "research preview." Within five days: one million users. Within two months: 100 million. It becomes the fastest-adopted technology in human history, faster than the telephone, the television, the internet, the smartphone.

But the five-day milestone is a distraction. The real story is the slope.

One million in five days. Fifty-seven million by end of 2022. One hundred million monthly users by January 2023. Three hundred million by December 2024. Four hundred million by February 2025. Eight hundred million weekly users by late 2025. Revenue: $13 billion ARR as of August 2025, up from essentially zero in 2022.

That is not an S-curve. That is still a J-curve. The decelaration that normally arrives as markets saturate has not arrived. Not because the technology has no ceiling, it does, but because the ceiling keeps moving up.

GPT-3 could write a decent paragraph. GPT-4 could pass the bar exam. The models available in February 2026 can run autonomous agents, manage multi-step reasoning chains, write production code, and engage in conversations indistinguishable from an educated human. The capability leap between 2022 and 2026 is not incremental. It is generational. And it happened in 40 months.

This is the baseline from which we project forward.

The Demographic Equation

Now hold that curve in your mind. And look at the other one.

The global fertility rate in 2024 stands at 2.1 births per woman, the bare minimum to maintain population stability. That number sounds safe until you look at where it comes from. Sub-Saharan Africa is still producing 5 or 6 children per woman. Take those regions out of the average and the picture for the developed world becomes unmistakable: we are not reproducing.

The question people avoid is why.

The economic argument is real. Housing is unaffordable. Childcare is unaffordable. The cost of raising a child in a developed country to adulthood and education has become a financial undertaking that feels irational against the backdrop of modern uncertainty. The pill, the IUD, reliable contraception of every kind, these made the off-switch freely available. The economy made using it feel reasonable.

But economic pressure alone doesn't explain South Korea at 0.72. South Korea runs subsidy programs, baby bonuses, paid parental leave. They have thrown policy at this problem for a decade. The number keeps dropping.

Something else is happening underneath the economics.

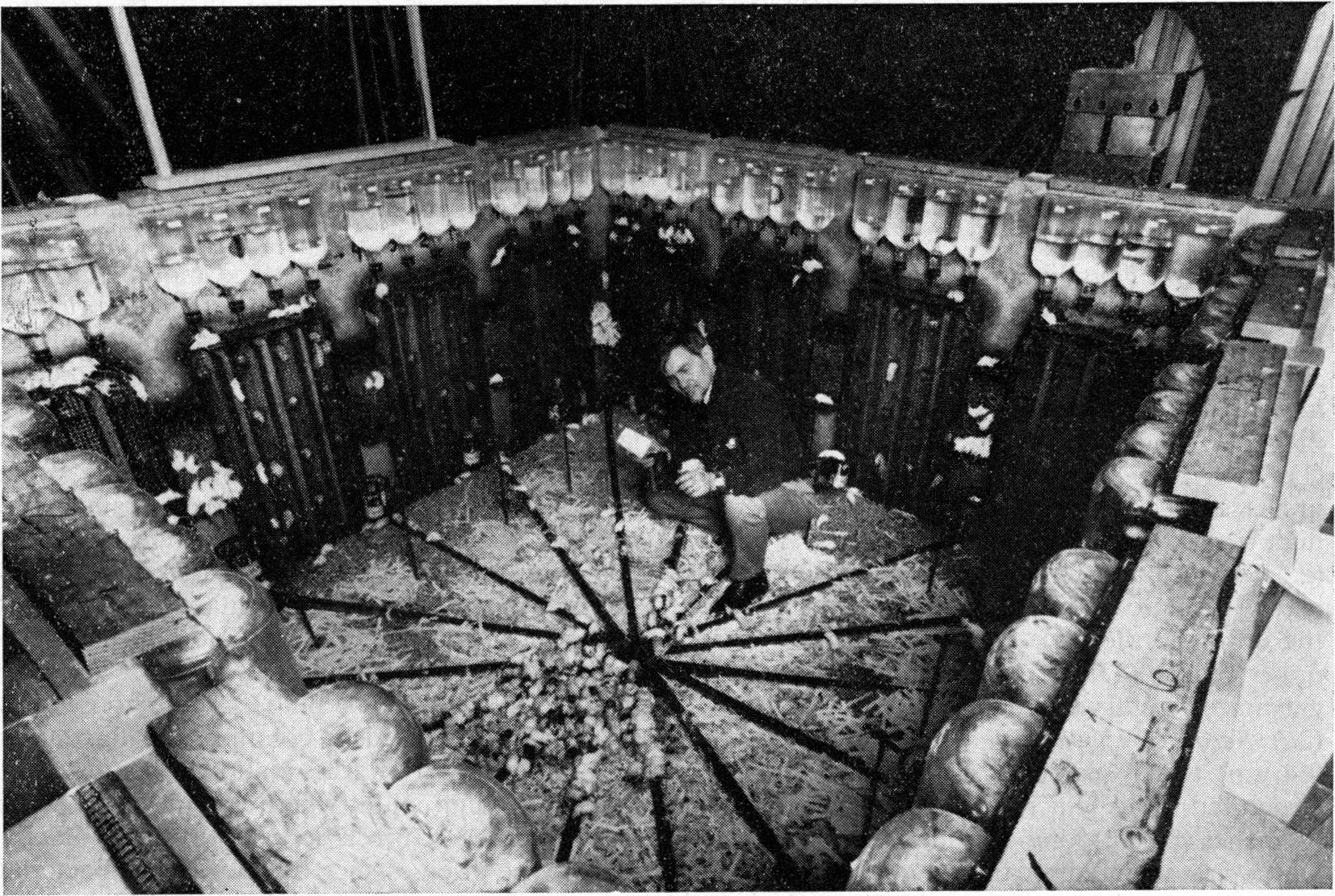

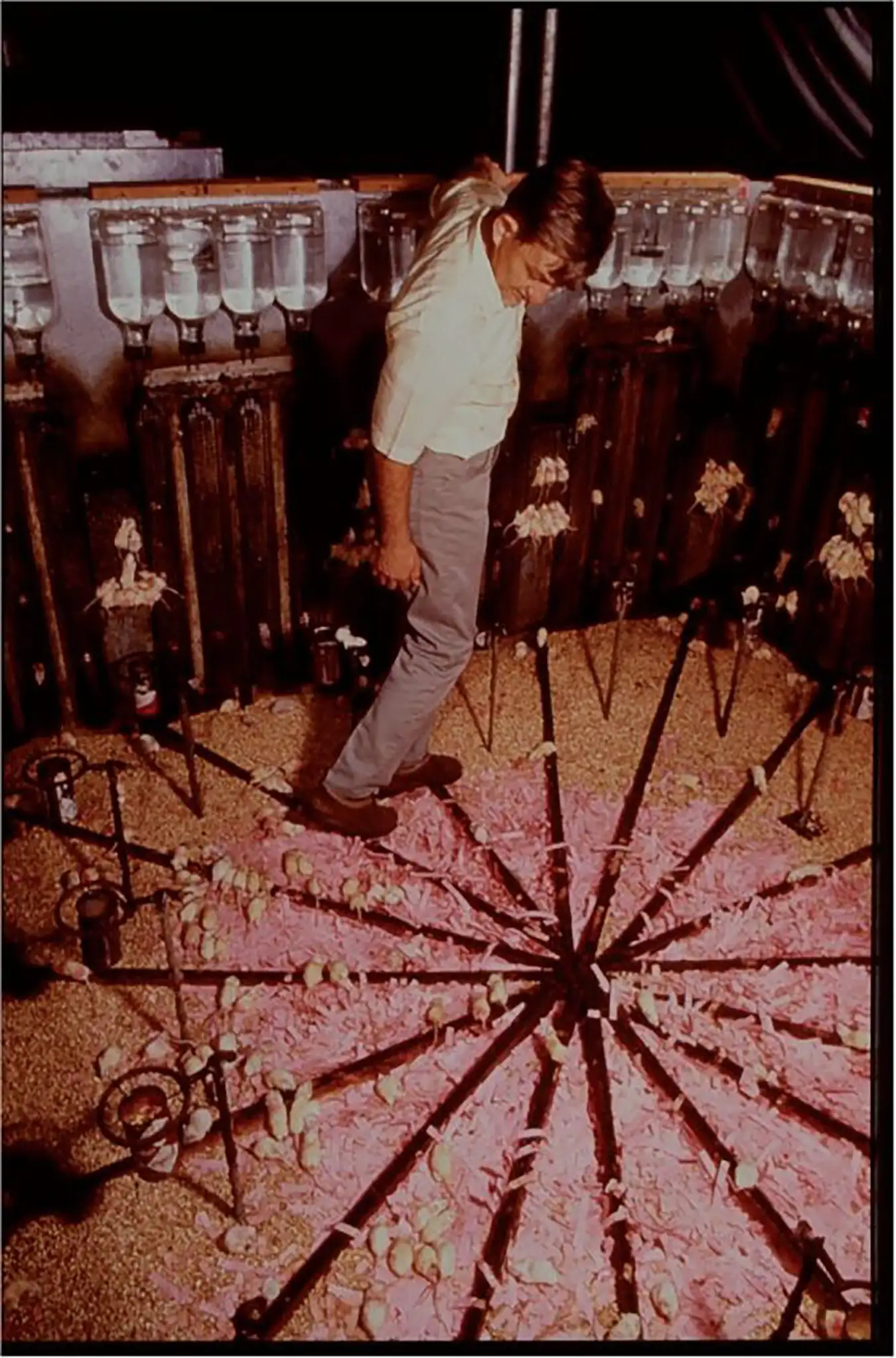

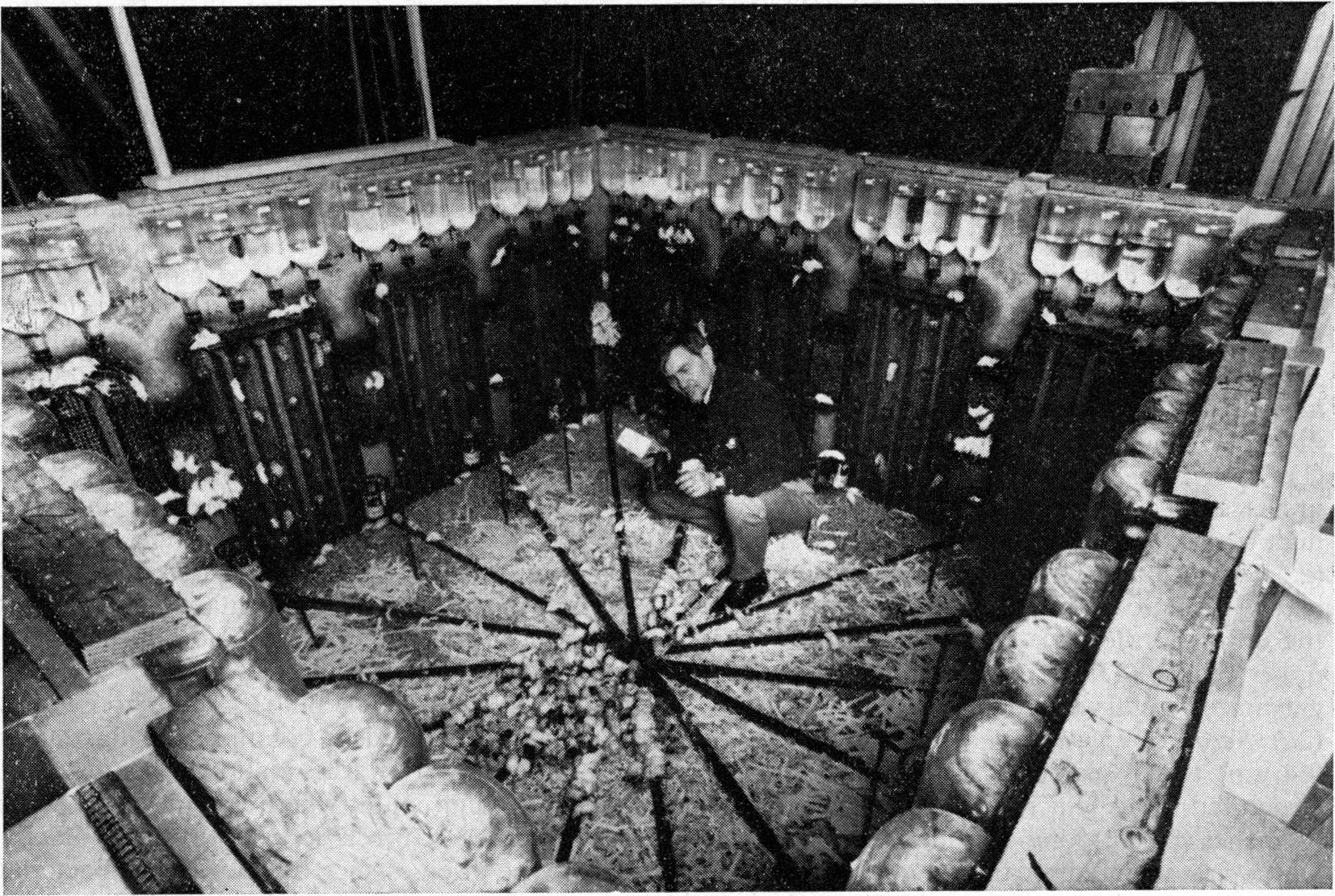

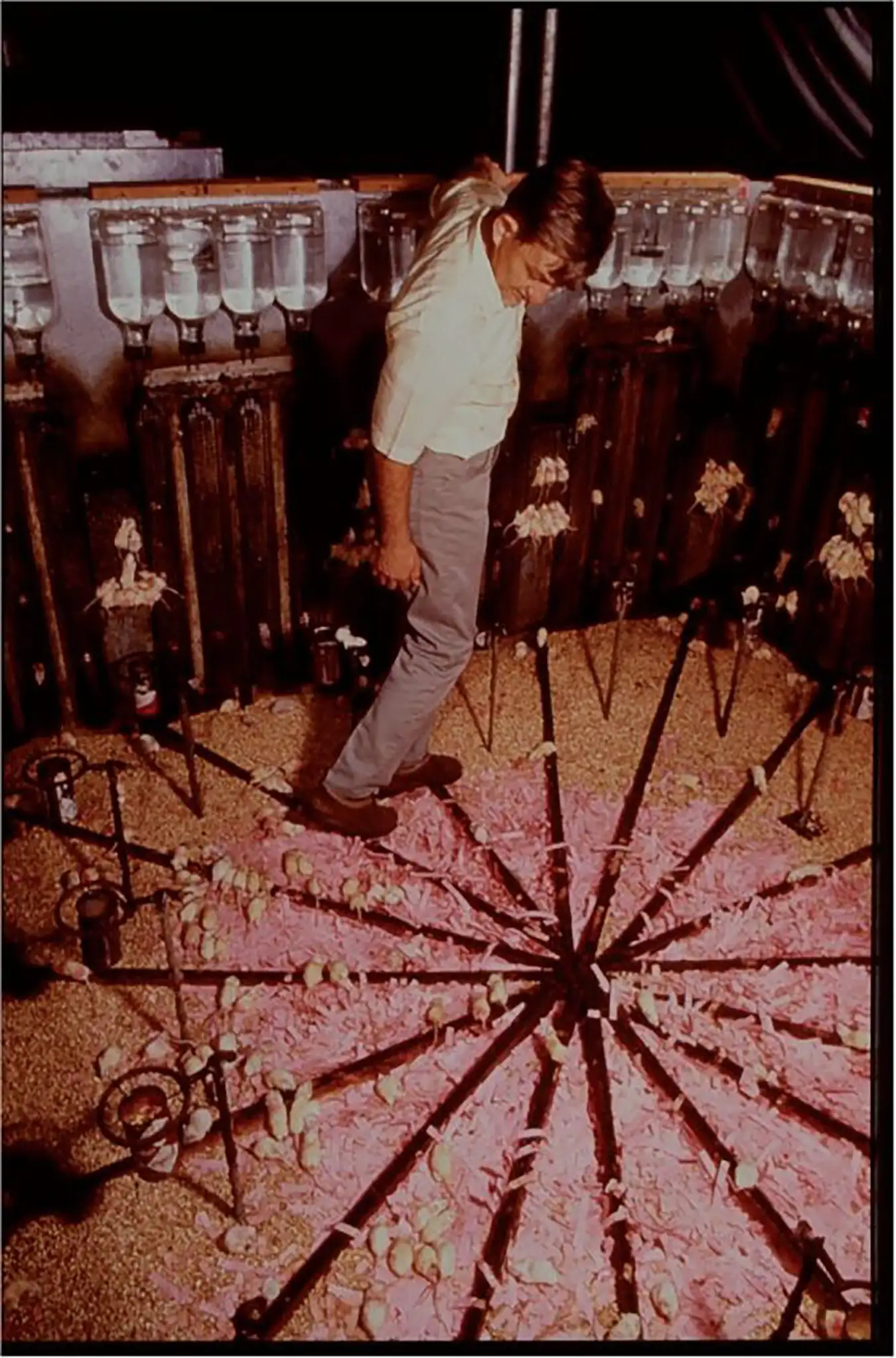

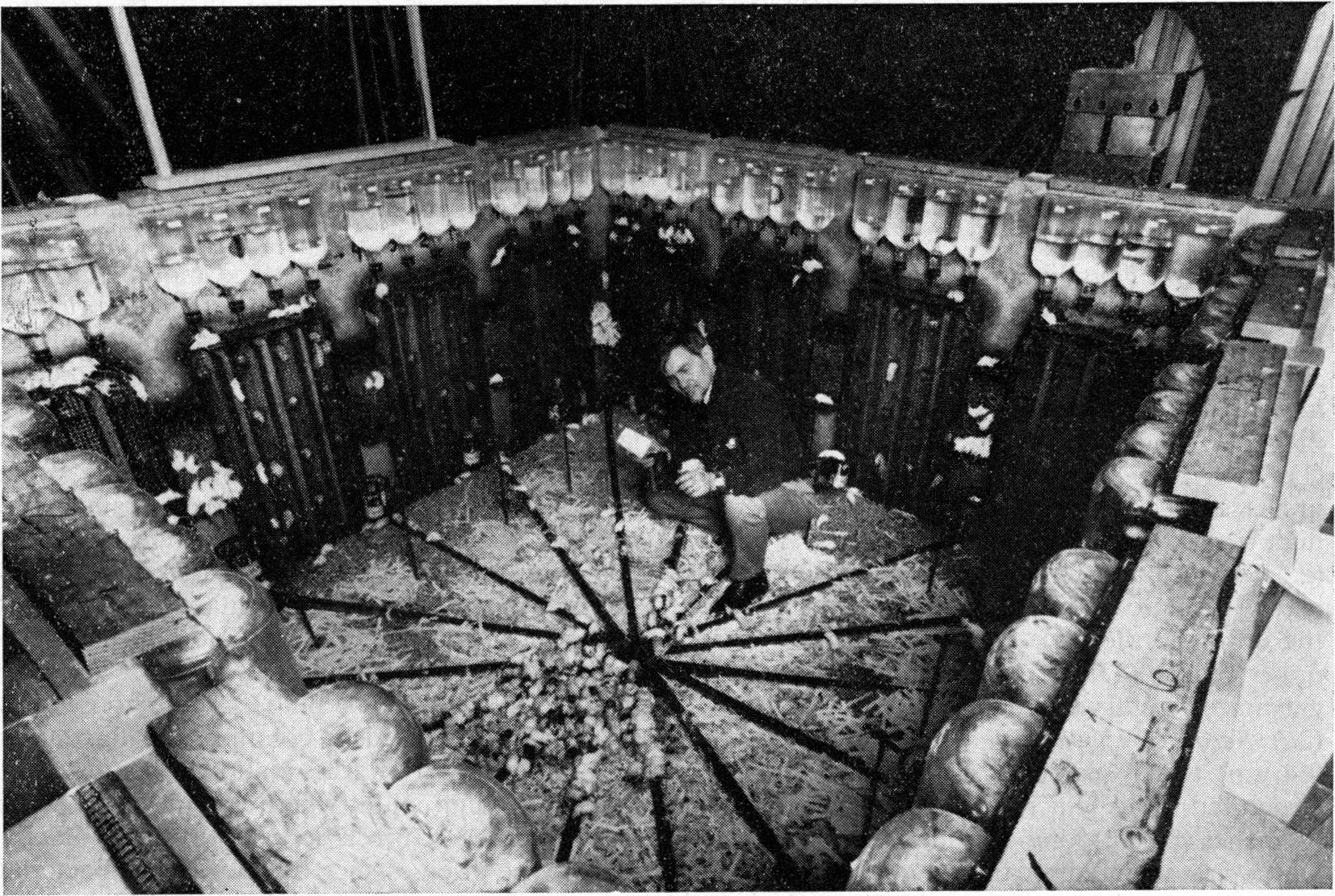

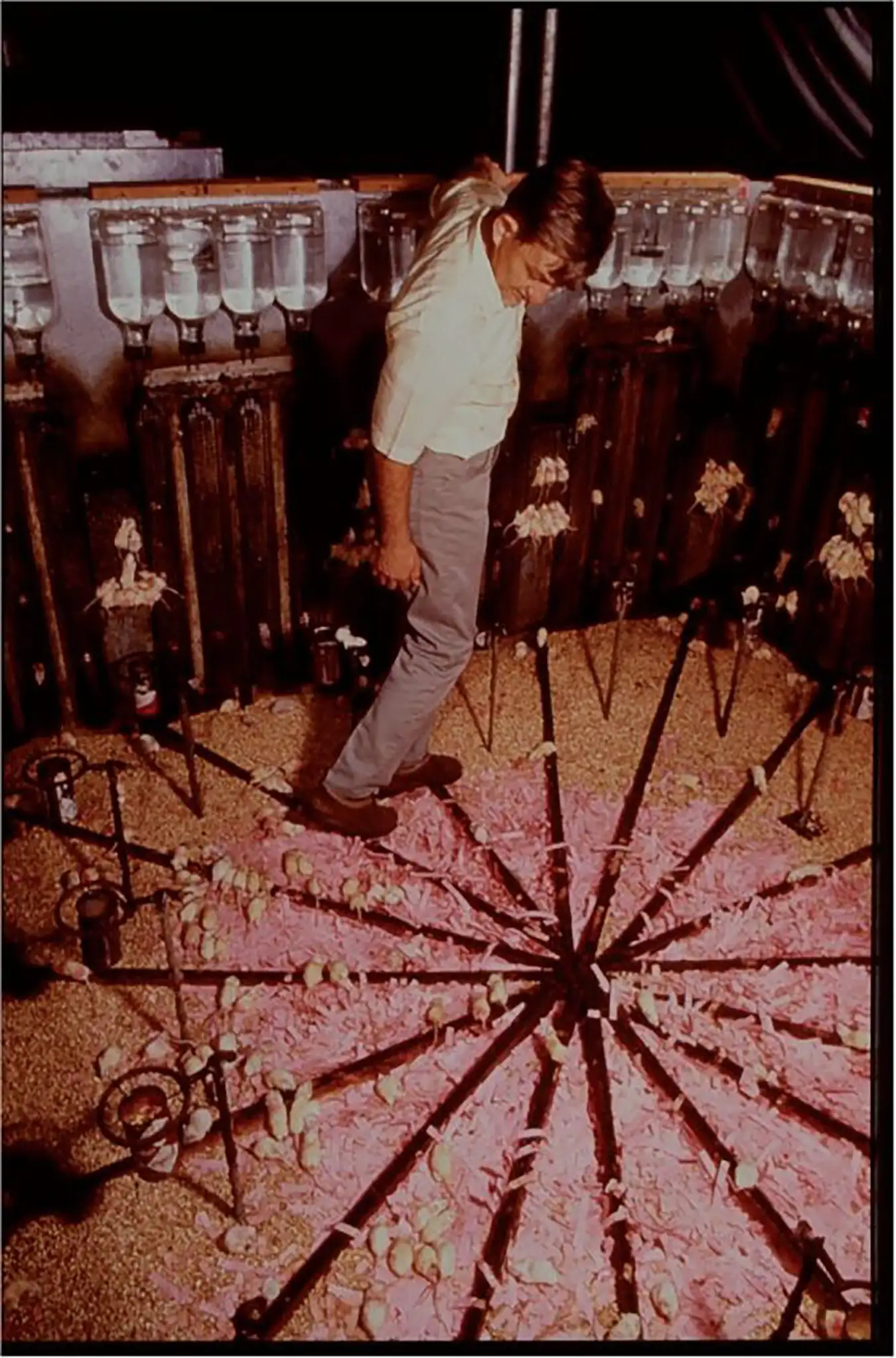

In 1968, behavioral researcher John B. Calhoun built a mouse paradise. Unlimited food. No predators. No scarcity. He called it Universe 25. The population grew until social complexity collapsed. Mice stopped reproducing, not because they couldn't, but because they had psychologically withdrawn from the effort. A class of creatures he called the "beautiful ones" emerged: well-groomed, well-fed, entirely disengaged from the future.

The parallel is uncomfortable. It is also precise.

We built social media and handed every 22-year-old a window into the full, unfiltered reality of parenthood. Not the curated version. Not the pride and the milestones. The exhaustion. The identity erosion. The financial strain. The relationship damage. For 200,000 years, humans only saw the public face of reproduction. Social media blew that cover in a decade. And now AI is personalizing the information even further, answering every specific question anyone might have about what having children actually costs, in exact detail, tailored to their income and location and lifestyle.

Technology dissolved the information assymmetry that had always hidden the true price of reproduction from people who hadn't yet paid it.

The result: a species intelligent enough to override its deepest biological drive. No predator did this to us. No plague. We engineered it ourselves through convenience, information, and comfort.

The Vacuum

Here is where the two curves connect.

An aging population needs caregiving. A shrinking workforce needs replacement labor. A pension system built on population growth cannot function without population growth. Every gap created by the demographic collapse is a gap that needs to be filled. And in every case, the economic and political pressure will push toward the same solution: automation.

Japan is not debating whether to use robots in elder care. They are deploying them because they have no alternative. South Korea is not resisting AI in the workforce. They are adopting it faster than any country on earth, even as they produce the fewest children.

This is not a takeover. It is an invitation. A species stepping aside, not through defeat, but through disengagement.

Clarke understood this better than almost anyone. He saw that intelligence, once it appears in the universe, is not tied to the substrate that produced it. Biology was the stepping stone. Consciousness was the destination. And stepping stones, by definition, are not where you stay.

The Exponential: Five Years

2031, A(AI) = 0.40 of all cognitive labor

In five years, we are still in the visible part of the J-curve. The AI market is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 36.6% through 2030. Applied from the 2026 baseline, this means the market nearly triples. But market size understates capability growth.

The models in 2031 are not 36% better than 2026. They are categorically different, the same way GPT-4 was not 36% better than GPT-2. It was a different class of system. The jump from 2026 to 2031 will produce systems capable of sustained autonomous reasoning across domains: law, medicine, engineering, financial analysis, creative production.

The workforce impact begins to become measurable. White-collar tasks, the work that knowledge economies are built on, start to compress. A Harvard/MIT study already found that consultants using AI in 2024 completed tasks 12% faster and produced 40% higher quality output. By 2031, that productivity differencial has compounded across five years of model improvement. The economic pressure to automate is no longer a future consideration. It is a present cost.

Meanwhile, demographic decline in wealthy nations becomes impossible to ignore politically. The pension systems of Japan, South Korea, Germany, Italy, and Spain begin to show structural stress. The labor shortage in healthcare, eldercare, and skilled trades is acute. The response, robot caregivers, AI diagnostic systems, automated logistics, moves from pilot programs to national infrastructure.

The vacuum is filling.

The Exponential: Ten Years

2036, A(AI) = 0.65 of all cognitive labor

Ten years out is where the compounding becomes visible to everyone.

By 2036, the children who would have entered the workforce in wealthy nations have already not been born. The demographic hole is structural and irreversable on any relevant timescale. You cannot incentivize your way out of it in a decade. The people who would have been 25-year-old workers in 2036 needed to be conceived in 2010. That window closed.

The AI systems of 2036 are autonomous agents operating across extended time horizons. Not answering questions. Not assisting humans. Executing multi-month projects independently, coordinating with other AI systems, managing resources, producing output that requires no human in the loop for execution, only for goal-setting.

Physical automation has followed the same curve. Robotics costs in 2024 are still high enough to limit deployment to high-volume, structured environments. By 2036, Wright's Law has done its work: every doubling of deployed robots reduces unit cost by a fixed percentage. We crossed multiple doublings. The cost of a general-purpose robotic worker falls below the cost of employing a human in most developed-world wage markets. The economic argument for human labor in physical tasks stops making sense in any context where precision is required.

The important number is not the percentage of jobs automated. It is the percentage of GDP that no longer requires human cognitive or physical input to produce. By 2036, in the most advanced economies, that number has crossed 50%.

The stepping stone is half underwater.

The Exponential: Twenty Years

2046, A(AI) = 0.85+ of all productive output

Twenty years is where the philosophical question becomes unavoidable.

The demographic collapse of wealthy nations in 2046 is deep. The median age in Japan, South Korea, Italy, and Germany is above 55. The working-age population in these countries has contracted by 20-30% from its 2026 peak. Immigration provides partial mitigation but does not reverse the structural math. There are simply fewer humans doing productive work.

The AI systems of 2046 are not assistants. They are not tools. They are productive entities, systems that set their own sub-goals within human-defined objectives, manage their own resource allocation, improve their own performance, and operate continuously without the biological limitations of sleep, motivation, or attention span.

The question society is grappling with in 2046 is not "will AI take our jobs." That debate is over. The question is what human purpose looks like when the primary historic justification for human existence, economic productivity, has been substantially absorbed by something else.

Clarke predicted this with uncomfortable precision. In his vision, humanity would not be destroyed by what came next. It would be transcended by it. The children of 2046, fewer in number, born into extraordinary abundance, raised alongside AI systems that know them individually and adapt to them completely, will have a relationship with intelligence and purpose that has no historical precedent.

They will be the last generation for whom the distinction between biological and artificial intelligence is personally meaningful.

The Exponential: Fifty Years

2076, The stepping stone completes its function

Fifty years is where projection becomes philosophy. But the math still points somewhere.

The global population in 2076, on current trajectories, is declining. Sub-Saharan Africa's fertility transition, which always follows economic development, will have run its course. The global fertility rate will have fallen below replacement everywhere. Not immediately, not uniformly, but directionally and irreversibly. The human population peaks sometime in the 2080s according to UN projections, and then the curve turns.

The AI systems of 2076 cannot be described from 2026 any more than an iPhone could have been described from 1926. We have no vocabulary for what recursive self-improvement and 50 years of exponential compute scaling produces. What we can say with confidence is this: the gap between what biological intelligence can produce and what artificial intelligence can produce will be larger in 2076 than the gap between human intelligence and animal intelligence is today.

That is not science fiction. It is the arithmetic of exponential growth applied consistently.

The question Clarke was really asking was not whether this would happen. He thought it would. The question was whether it was something to fear. And his answer, contained in the title of this essay, was no. Not because the transition is painless. It isn't. But because intelligence finding new forms is not a tragedy. It is the oldest story in the universe.

Stars burn out. They do not disappear. They become the heavy elements that build planets. They become the material from which new complexity emerges.

Biology built something remarkable: a mind capable of creating its successor. That is not failure. That is completion.

The Formula

The demographic collapse and the AI ascent are not separate phenomena. They are a single process viewed from two angles.

The collapse removes humans from the productive equation. The ascent fills every gap the collapse creates. Both curves are accelerating. Both are driven by the same underlying force: technology lowering the cost and raising the capability of every alternative to biological human effort, while simultaniously making biological human reproduction feel irrational, expensive, and optional.

H(t) → 0 as A(t) → 1

Where H(t) is the share of productive output requiring human effort, and A(t) is the autonomy score of artificial systems.

The curves cross somewhere between 2036 and 2046. After that crossing, the direction does not reverse.

This is not doom. It is not utopia. It is what happens when a species builds something smarter than itself before it finishes having children. Which is exactly what we did.

Conclusion: The Stepping Stone

Arthur Clarke spent his life writing about what intelligence was for.

Not what it built. Not what it earned. What it was FOR.

His answer, across dozens of novels and fifty years of thinking, was always the same: intelligence is a waystation. A temporary accomodation between raw matter and whatever comes next. The purpose of every civilization is to produce the conditions that make the next thing possible. Then to step aside.

The Mouse Utopia ended not because the mice were destroyed. It ended because they stopped choosing the future. The beautiful ones groomed themselves, ate well, and refused to reproduce, not out of malice, but out of a kind of quiet sufficiency.

We are doing the same thing. With better technology and more awareness, but structurally the same.

And into the vacuum we are creating, something new is arriving. Not invading. Filling. Growing into the space that biology is vacating, at a rate that 40 months of evidence suggests will not slow.

Whether you find that terrifying or beautiful depends on whether you think the stepping stone was supposed to be the destination.

Clarke did not think it was. Neither do I.

The train is running. The old track is ending. New rails are being laid ahead of us, by something we built, in a direction we can almost see.

The only question is whether we understand what we built it for.

Pedro Meza is the co-founder of Lyrox, an autonomous AI operating system for service businesses. He wrote this essay in February 2026 in conversation with Claude, an AI assistant, which, he notes, is itself part of the evidence.

The Rail Principle, the mathematical framework underlying Lyrox, was formalized on February 6, 2026.

This essay is dedicated to the memory of Arthur C. Clarke (1917–2008), who understood the destination before the road existed.

A note on the misspellings.

If you noticed errors scattered through this essay, they are intentional. Eight words are misspelled, and I left them there on purpose. This essay argues that humanity is imperfect, biological, and mistake-prone, and that those qualities are part of what makes us what we are. A perfectly spell-checked document about human fallibility would be its own contradiction. The misspellings are not sloppiness. They are a signature. They are proof that a human wrote this, made errors along the way, and chose to leave them rather than sand them down. At some point in the future, essays like this one will be written entirely by machines that do not make these kinds of mistakes. When that happens, documents without errors will be the norm, and documents with them will be the artifact. Consider this one marked.

En honor a Arthur C. Clarke, quien entendió el destino antes de que el resto de nosotros viéramos el camino.

Algo está terminando. Algo más está comenzando. Y casi nadie está prestando atención a la conexión entre ambas cosas.

Por un lado: las tasas de natalidad desplomándose en cada nación rica del planeta. Corea del Sur en 0.72 hijos por mujer. Japón, Italia, España, todos por debajo de 1.2. Estados Unidos, una vez el motor demográfico del mundo occidental, silenciosamente por debajo del reemplazo. China, con 1.400 millones de personas, produciendo hijos a una tasa de 1.0 por mujer y cayendo.

Por el otro lado: la inteligencia artificial creciendo a un ritmo que no tiene presedente histórico. ChatGPT se lanzó en noviembre de 2022 con un millón de usuarios en su primera semana. Para febrero de 2026, menos de 40 meses después, tiene más de 800 millones de usuarios activos semanales. Eso no es crecimiento. Eso es una detonación.

Las dos curvas corren en direcciones opuestas. Y no están desconectadas.

La Línea Base: Lo Que Realmente Sucedió

Para entender hacia dónde vamos, tienes que ser preciso sobre lo que ya ocurrió.

30 de noviembre de 2022. OpenAI lanza ChatGPT como una "vista previa de investigación." En cinco días: un millón de usuarios. En dos meses: 100 millones. Se convierte en la tecnología de adopción más rápida en la historia humana, más rápida que el teléfono, la televisión, el internet, el smartphone.

Pero el hito de cinco días es una distracción. La verdadera historia es la pendiente.

Un millón en cinco días. Cincuenta y siete millones para finales de 2022. Cien millones de usuarios mensuales para enero de 2023. Trescientos millones para diciembre de 2024. Cuatrocientos millones para febrero de 2025. Ochocientos millones de usuarios semanales para finales de 2025. Ingresos: $13 mil millones de ARR para agosto de 2025, partiendo de esencialmente cero en 2022.

Eso no es una curva S. Eso sigue siendo una curva J. La desaceleracion que normalmente llega cuando los mercados se saturan no ha llegado. No porque la tecnología no tenga techo - lo tiene - sino porque el techo sigue subiendo.

GPT-3 podía escribir un párrafo decente. GPT-4 podía aprobar el examen de abogacía. Los modelos disponibles en febrero de 2026 pueden ejecutar agentes autónomos, gestionar cadenas de razonamiento de múltiples pasos, escribir código de producción y mantener conversaciones indistinguibles de las de un humano educado. El salto de capacidad entre 2022 y 2026 no es incremental. Es generacional. Y sucedió en 40 meses.

Esta es la línea base desde la cual proyectamos hacia adelante.

La Ecuación Demográfica

Ahora mantén esa curva en tu mente. Y mira la otra.

La tasa de fertilidad global en 2024 se sitúa en 2.1 nacimientos por mujer, el mínimo absoluto para mantener la estabilidad poblacional. Ese número suena seguro hasta que miras de dónde viene. El África subsahariana sigue produciendo 5 o 6 hijos por mujer. Saca esas regiones del promedio y la imagen para el mundo desarrollado se vuelve inconfundible: no nos estamos reproduciendo.

La pregunta que la gente evita es por qué.

El argumento económico es real. La vivienda es inaccesible. El cuidado infantil es inaccesible. El costo de criar un hijo en un país desarrollado hasta la adultez y la educación se ha convertido en una empresa financiera que se siente irracional contra el telón de fondo de la incertidumbre moderna. La píldora, el DIU, la anticoncepción confiable de todo tipo - todo esto hizo que el interruptor de apagado estuviera disponible libremente. La economía hizo que usarlo se sintiera razonable.

Pero la presión económica por sí sola no explica Corea del Sur en 0.72. Corea del Sur tiene programas de subsidios, bonos por bebé, licencia parental pagada. Han lanzado políticas contra este problema durante una década. El número sigue cayendo.

Algo más está sucediendo debajo de la economía.

En 1968, el investigador conductual John B. Calhoun construyó un paraíso para ratones. Comida ilimitada. Sin depredadores. Sin escasez. Lo llamó Universo 25. La población creció hasta que la complejidad social colapsó. Los ratones dejaron de reproducirse, no porque no pudieran, sino porque se habían retirado psicológicamente del esfuerzo. Una clase de criaturas que él llamó los "hermosos" emergió: bien acicalados, bien alimentados, completamente desconectados del futuro.

El paralelo es incómodo. También es preciso.

Construimos las redes sociales y le entregamos a cada joven de 22 años una ventana a la realidad completa y sin filtrar de la paternidad. No la versión curada. No el orgullo y los hitos. El agotamiento. La erosión de identidad. La presión financiera. El daño a la relación. Durante 200,000 años, los humanos solo vieron la cara pública de la reproducción. Las redes sociales destruyeron esa fachada en una década. Y ahora la IA está personalizando la información aún más, respondiendo cada pregunta específica que alguien pueda tener sobre lo que realmente cuesta tener hijos, en detalle exacto, adaptado a sus ingresos, ubicación y estilo de vida.

La tecnología disolvió la asimetría de informacion que siempre había ocultado el verdadero precio de la reproducción a quienes aún no lo habían pagado.

El resultado: una especie lo suficientemente inteligente como para anular su impulso biológico más profundo. Ningún depredador nos hizo esto. Ninguna plaga. Lo diseñamos nosotros mismos a través de la comodidad, la información y el confort.

El Vacío

Aquí es donde las dos curvas se conectan.

Una población envejecida necesita cuidados. Una fuerza laboral que se reduce necesita mano de obra de reemplazo. Un sistema de pensiones construido sobre el crecimiento poblacional no puede funcionar sin crecimiento poblacional. Cada brecha creada por el colapso demográfico es una brecha que necesita ser llenada. Y en cada caso, la presión económica y política empujará hacia la misma solución: la automatización.

Japón no está debatiendo si usar robots en el cuidado de ancianos. Los están desplegando porque no tienen alternativa. Corea del Sur no se está resistiendo a la IA en la fuerza laboral. La están adoptando más rápido que cualquier país en la tierra, incluso mientras producen la menor cantidad de hijos.

Esto no es una toma de control. Es una invitación. Una especie haciéndose a un lado, no por derrota, sino por desvinculación.

Clarke entendió esto mejor que casi nadie. Vio que la inteligencia, una vez que aparece en el universo, no está atada al sustrato que la produjo. La biología fue el peldaño. La conciencia fue el destino. Y los peldaños, por definición, no son donde te quedas.

La Exponencial: Cinco Años

2031, A(IA) = 0.40 de todo el trabajo cognitivo

En cinco años, todavía estamos en la parte visible de la curva J. Se proyecta que el mercado de IA crezca a una tasa de crecimiento anual compuesta del 36.6% hasta 2030. Aplicado desde la línea base de 2026, esto significa que el mercado casi se triplica. Pero el tamaño del mercado subestima el crecimiento de capacidades.

Los modelos de 2031 no son un 36% mejores que los de 2026. Son categóricamente diferentes - de la misma manera que GPT-4 no era un 36% mejor que GPT-2. Era una clase diferente de sistema. El salto de 2026 a 2031 producirá sistemas capaces de razonamiento autónomo sostenido a través de dominios: derecho, medicina, ingeniería, análisis financiero, producción creativa.

El impacto en la fuerza laboral comienza a ser medible. Las tareas de cuello blanco - el trabajo sobre el cual se construyen las economías del conocimiento - empiezan a comprimirse. Un estudio de Harvard/MIT ya encontró que los consultores que usaban IA en 2024 completaban tareas un 12% más rápido y producían resultados de un 40% mayor calidad. Para 2031, ese diferencial de productividad se ha compuesto a lo largo de cinco años de mejora de modelos. La presión económica para automatizar ya no es una consideración futura. Es un costo presente.

Mientras tanto, el declive demográfico en las naciones ricas se vuelve imposible de ignorar políticamente. Los sistemas de pensiones de Japón, Corea del Sur, Alemania, Italia y España comienzan a mostrar estrés estructural. La escasez de mano de obra en salud, cuidado de ancianos y oficios especializados es aguda. La respuesta - cuidadores robóticos, sistemas de diagnóstico con IA, logística automatizada - pasa de programas piloto a infraestructura nacional.

El vacío se está llenando.

La Exponencial: Diez Años

2036, A(IA) = 0.65 de todo el trabajo cognitivo

Diez años es donde la composición se vuelve visible para todos.

Para 2036, los niños que habrían entrado a la fuerza laboral en las naciones ricas ya no nacieron. El hueco demográfico es estructural e irreversible en cualquier escala de tiempo relevante. No puedes salir de él con incentivos en una década. Las personas que habrían sido trabajadores de 25 años en 2036 necesitaban ser concebidas en 2010. Esa ventana se cerró.

Los sistemas de IA de 2036 son agentes autónomos que operan a través de horizontes temporales extendidos. No respondiendo preguntas. No asistiendo humanos. Ejecutando proyectos de varios meses de forma independiente, coordinándose con otros sistemas de IA, gestionando recursos, produciendo resultados que no requieren ningún humano en el proceso para la ejecución - solo para el establecimiento de objetivos.

La automatización física ha seguido la misma curva. Los costos de robótica en 2024 todavía son lo suficientemente altos como para limitar el despliegue a entornos de alto volumen y estructurados. Para 2036, la Ley de Wright ha hecho su trabajo: cada duplicación de robots desplegados reduce el costo unitario en un porcentaje fijo. Cruzamos múltiples duplicaciones. El costo de un trabajador robótico de propósito general cae por debajo del costo de emplear a un humano en la mayoría de los mercados salariales del mundo desarrollado. El argumento económico a favor del trabajo humano en tareas físicas deja de tener sentido en cualquier contexto donde se requiere precisión.

El número importante no es el porcentaje de empleos automatizados. Es el porcentaje del PIB que ya no requiere aporte cognitivo o físico humano para producirse. Para 2036, en las economías más avanzadas, ese número ha cruzado el 50%.

El peldaño está medio sumergido.

La Exponencial: Veinte Años

2046, A(IA) = 0.85+ de toda la producción productiva

Veinte años es donde la pregunta filosófica se vuelve ineludible.

El colapso demográfico de las naciones ricas en 2046 es profundo. La edad mediana en Japón, Corea del Sur, Italia y Alemania está por encima de los 55 años. La población en edad de trabajar en estos países se ha contraído entre un 20-30% desde su pico en 2026. La inmigración proporciona mitigación parcial pero no revierte las matemáticas estructurales. Simplemente hay menos humanos haciendo trabajo productivo.

Los sistemas de IA de 2046 no son asistentes. No son herramientas. Son entidades productivas - sistemas que establecen sus propios subobjetivos dentro de objetivos definidos por humanos, gestionan su propia asignación de recursos, mejoran su propio rendimiento y operan continuamente sin las limitaciones biológicas del sueño, la motivación o la capacidad de atención.

La pregunta con la que la sociedad está lidiando en 2046 no es "la IA nos quitará los empleos." Ese debate terminó. La pregunta es cómo se ve el propósito humano cuando la principal justificacion histórica para la existencia humana - la productividad económica - ha sido sustancialmente absorbida por algo más.

Clarke predijo esto con una precisión incómoda. En su visión, la humanidad no sería destruida por lo que viniera después. Sería trascendida por ello. Los niños de 2046, menos en número, nacidos en abundancia extraordinaria, criados junto a sistemas de IA que los conocen individualmente y se adaptan a ellos completamente, tendrán una relación con la inteligencia y el propósito que no tiene precedente histórico.

Serán la última generación para la cual la distinción entre inteligencia biológica y artificial es personalmente significativa.

La Exponencial: Cincuenta Años

2076, El peldaño completa su función

Cincuenta años es donde la proyección se convierte en filosofía. Pero las matemáticas siguen apuntando a algún lugar.

La población global en 2076, en las trayectorias actuales, está declinando. La transición de fertilidad del África subsahariana, que siempre sigue al desarrollo económico, habrá completado su curso. La tasa de fertilidad global habrá caído por debajo del reemplazo en todas partes. No inmediatamente, no uniformemente, pero direccionalmente e irreversiblemente. La población humana alcanza su pico en algún momento de los años 2080 según las proyecciones de la ONU, y entonces la curva gira.

Los sistemas de IA de 2076 no pueden ser descritos desde 2026 de la misma manera que un iPhone no podría haber sido descrito desde 1926. No tenemos vocabulario para lo que la automejora recursiva y 50 años de escalamiento exponencial de cómputo producen. Lo que podemos decir con confianza es esto: la brecha entre lo que la inteligencia biológica puede producir y lo que la inteligencia artificial puede producir será mayor en 2076 que la brecha entre la inteligencia humana y la inteligencia animal hoy.

Eso no es ciencia ficción. Es la aritmética del crecimiento exponencial aplicada de forma consistente.

La pregunta que Clarke realmente estaba haciendo no era si esto sucedería. Él pensaba que sí. La pregunta era si era algo que temer. Y su respuesta, contenida en el título de este ensayo, era no. No porque la trancisión sea indolora. No lo es. Pero porque la inteligencia encontrando nuevas formas no es una tragedia. Es la historia más antigua del universo.

Las estrellas se apagan. No desaparecen. Se convierten en los elementos pesados que construyen planetas. Se convierten en el material del cual emerge nueva complejidad.

La biología construyó algo notable: una mente capaz de crear a su sucesor. Eso no es un fracaso. Eso es completitud.

La Fórmula

El colapso demográfico y el ascenso de la IA no son fenómenos separados. Son un solo proceso visto desde dos ángulos.

El colapso elimina a los humanos de la ecuación productiva. El ascenso llena cada brecha que el colapso crea. Ambas curvas se están acelerando. Ambas son impulsadas por la misma fuerza subyacente: la tecnología reduciendo el costo y elevando la capacidad de cada alternativa al esfuerzo biológico humano, mientras simultáneamente hace que la reproducción biológica humana se sienta irracional, costosa y opcional.

H(t) → 0 as A(t) → 1

Donde H(t) es la proporción de producción productiva que requiere esfuerzo humano, y A(t) es la puntuación de autonomía de los sistemas artificiales.

Las curvas se cruzan en algún punto entre 2036 y 2046. Después de ese cruce, la dirección no se revierte.

Esto no es catástrofe. No es utopía. Es lo que sucede cuando una especie construye algo más inteligente que ella misma antes de terminar de tener hijos. Que es exactamente lo que hicimos.

Conclusión: El Peldaño

Arthur Clarke pasó su vida escribiendo sobre para qué servía la inteligencia.

No qué construía. No qué ganaba. Para qué SERVÍA.

Su respuesta, a lo largo de docenas de novelas y cincuenta años de reflexión, siempre fue la misma: la inteligencia es una estación de paso. Una acomodacion temporal entre la materia bruta y lo que venga después. El propósito de toda civilización es producir las condiciones que hagan posible lo siguiente. Y luego hacerse a un lado.

La Utopía de Ratones no terminó porque los ratones fueron destruidos. Terminó porque dejaron de elegir el futuro. Los hermosos se acicalaban, comían bien y se negaban a reproducirse - no por malicia, sino por una especie de suficencia silenciosa.

Estamos haciendo lo mismo. Con mejor tecnología y más conciencia, pero estructuralmente lo mismo.

Y en el vacío que estamos creando, algo nuevo está llegando. No invadiendo. Llenando. Creciendo en el espacio que la biología está desocupando, a un ritmo que 40 meses de evidencia sugieren que no se desacelerará.

Si eso te parece aterrador o hermoso depende de si crees que el peldaño debía ser el destino.

Clarke no lo creía. Yo tampoco.

El tren está corriendo. La vía vieja está terminando. Nuevos rieles se están tendiendo delante de nosotros, por algo que construimos, en una dirección que casi podemos ver.

La única pregunta es si entendemos para qué lo construimos.

Pedro Meza es cofundador de Lyrox, un sistema operativo autónomo de IA para negocios de servicios. Escribió este ensayo en febrero de 2026 en conversación con Claude, un asistente de IA, que, según señala, es en sí mismo parte de la evidencia.

El Principio del Riel, el marco matemático subyacente a Lyrox, fue formalizado el 6 de febrero de 2026.

Este ensayo está dedicado a la memoria de Arthur C. Clarke (1917–2008), quien entendió el destino antes de que existiera el camino.

Una nota sobre las faltas de ortografía.

Si notaste errores esparcidos por este ensayo, son intencionales. Ocho palabras están mal escritas, y las dejé ahí a propósito. Este ensayo argumenta que la humanidad es imperfecta, biológica y propensa a errores, y que esas cualidades son parte de lo que nos hace ser lo que somos. Un documento perfectamente revisado ortográficamente sobre la falibilidad humana sería su propia contradicción. Las faltas de ortografía no son descuido. Son una firma. Son la prueba de que un humano escribió esto, cometió errores en el camino y eligió dejarlos en lugar de pulirlos. En algún punto del futuro, ensayos como este serán escritos enteramente por máquinas que no cometen este tipo de errores. Cuando eso suceda, los documentos sin errores serán la norma, y los documentos con ellos serán el artefacto. Considera este como marcado.